So I get the question all the time..EVen I wana build it if I can hahaha...

Here are some tips and tricks :)

Courtesy of

ISSA

You get this all the time from your clients, right?

“My legs are bulging, but what about my butt?”

“I really want to shape up my butt more; how do I do it?”

We want to be strong and fit, but let’s face it; we also want a perfect butt, glutes or backside. It’s by far the most common thing my clients ask for, and I have the answer.

I won’t give you all this “fluffy” stuff that you see from Instagram girls who post pictures of their booty all day. Some of them may actually give good tips, but this is the ISSA, so let me give you the science behind glute training.

First, you need to understand the muscles involved. Those that give us that nice, curvy bottom include the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus.

A lot of our daily movements, like walking or running, involve these muscles, and yet, most people never train them specifically.

When you do train your gluteus muscles, it’s possible to achieve hypertrophy, or growth in the size of the muscles. The secret is to target each of the glute muscles and to progressively overload them with high intensity.

This can be achieved within any range of reps, but you get the best muscle hypertrophy results from a rep range of six to twelve and with a heavy resistance.

Can’t I Just Squat and Lunge?

From a lot of people who haven’t done their research, you’ll hear:

“Just squat more! And dead lift more!”

Squats, deadlifts, and lunges definitely hit the glutes, but they also target a lot of other muscles, like the quads, hamstrings, abs, and others.

Although some people may build a beautiful derriere from just squatting, deadlifting, and lunging, one size does not fit all and this approach may not work for everyone. For those who need a little extra help, or don't want to spend all their time in the squat rack, hit those glutes directly

If you want to really build an awesome tush, you need to hit it directly, with exercises that cause the highest percentage of muscle activation from the three gluteus muscles.

The glutes are most activated when the hips are near full extension, so focus on exercises that target the glutes and achieve this full range of motion.

Your Best Bets to Target the Glutes

Now, let’s get specific. What exactly are the best exercises for seeing growth in the glute muscles?

- Side plank abductions

- Single leg squats

- Hip bridges

- Kettle bell swings (with an emphasis on hip thrust with glute contraction)

- Hip external rotations

- Single-leg elevated hip thrusts

Most of these exercises achieve a 70% or greater maximal voluntary muscle contraction (MVIC). The higher that percentage, the more you’re working those glutes and the faster you’re moving toward bigger muscles.

Side plank abductions come out on top with 103% MVIC, and single leg squats are the next best with 82% MVIC .

Don’t Forget the Legs

From my own personal experience, I have seen the greatest results in glute muscle development when I added an additional, glute-intensive workout day.

But, I also include my legs because they are all related.

On Mondays I dedicate my workout to leg exercises that also hit the glutes:

- Heavy barbell squats

- Split lunges

- Hamstring curls

- Leg extensions

I dedicate my Friday or Saturday workout to strictly “booty building” and I put my glutes through the ringer.

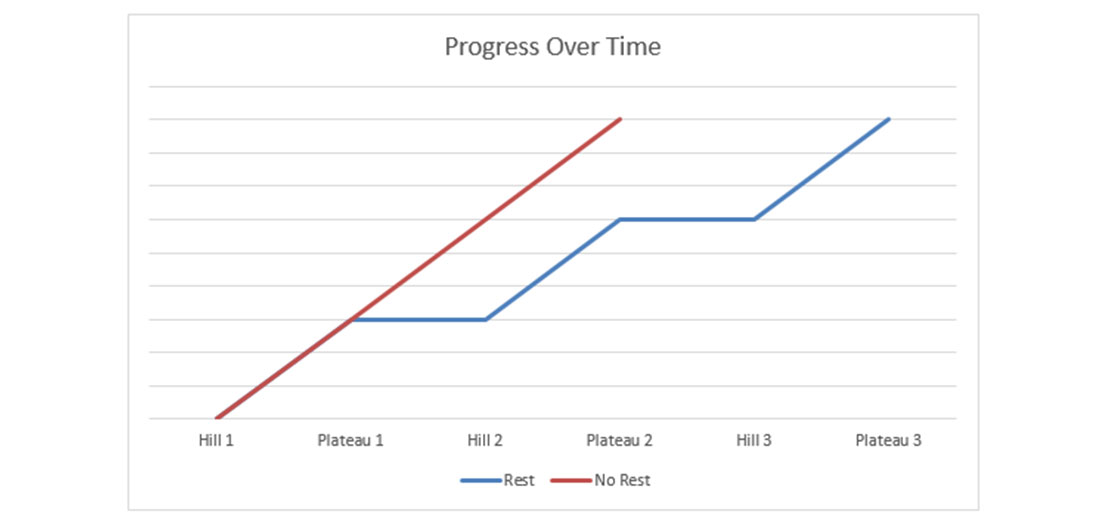

I attribute my progress to the progressive overload principle, which is the “gradual increase of stress placed upon the body during exercise training.”

This is the most important principle in strength training, and it gives you the best results in muscle growth and strength.

This is because our muscles increase in strength and size when they are forced to contract at tensions closest to their maximum.

To achieve this you can either:

- Perform more reps with the same amount of weight.

- Increase the resistance load and perform the same amount of reps.

- Add more sets of “work” to a specific muscle group.

Train the Glutes SPECIFICALLY

The takeaway lesson here is that squats and deadlifts are not a sure guarantee of a firm and curvy backside. You cannot simply squat and deadlift your way to a firm and curvy backside.

It’s a pretty simple principle: If I want to grow big, strong biceps, I have to train my biceps, not my triceps.

So, if your client wants to build bigger, stronger glutes? Train the heck out of the glutes, not just the other surrounding muscles in the legs.

I’ve had clients who say to me:

“I’m happy with my quad and hamstring development, but my glutes are not up to par. I want to build my glutes up more, but keep my quads and hamstrings the same size.”

A tough goal to achieve for sure, but totally possible. Most of the women who say this to me will report that they squat, deadlift, and lunge just as much as the guys.

This is exactly why their glutes are lagging behind the development of their quads and hamstrings – because most of those exercises are compound movements. The other muscles of the leg take over during the movement instead of giving the glutes their highest percent of muscle activation.

Lastly, the most important thing I tell my female clients who want bigger butts: Squats and lunges alone may not do the trick. You have to add specific, targeted glute exercises and workouts at least once a week.